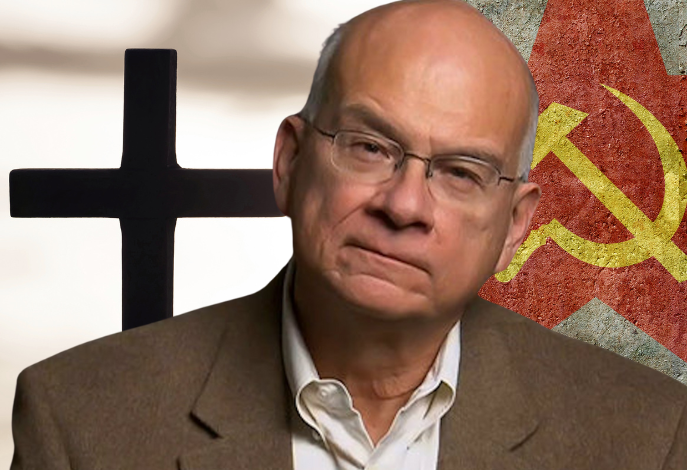

What Happened to Tim Keller?

Perhaps no one has done more to narrow the gap between progressive evangelicalism and mainstream evangelicalism than Tim Keller. Keller grew up in a mainline Lutheran church. As a teenager, during confirmation class, a young Lutheran cleric and social activist introduced him to a Christian version of social liberation grounded in a “spirit of love.” However, the Kellers soon started attending a conservative Methodist church which helped reinforce their son’s more traditional conception of God and the reality of hell.1 What he could not harmonize as a teenager—the ethics of the New Left and orthodox Christianity—he started learning to reconcile in college.

While attending Bucknell University, in his home state of Pennsylvania, Keller learned the “reigning ideologies of the time” from radical professors, including the “neo-Marxist critical theory of the Frankfurt School.”2 He was attracted to this “critique of American bourgeoisie society,” as well as social activism. Keller described himself and fellow students as wanting to “change the world” by rejecting things like “the military-industrial complex” and “a society of inequities and materialism.” Instead, they promoted “peace and understanding,” attended peace and civil rights marches, and shut down the college to debate the morality of the Cambodian invasion in 1970.3 Though things like segregation and “systemic violence … against blacks” bothered Keller before college, they became an occasion for him to doubt Christianity itself after his arrival.4

It was hard enough for the young student to maintain his faith while regularly hearing philosophical objections to it, living a “double life,” and struggling with deep depression.5 There were times he wondered if he was “just a cog in a machine” determined by his environment.6 However, the “spiritual crisis” he experienced as a student was also the result of a tension between his more activist “secular friends” and Christians who considered Martin Luther King Jr. to be a social threat.7 Keller had a dilemma.

While he was emotionally drawn to “social justice,” its practitioners were “moral relativists” who could not ground their convictions in an objective standard. When Christian evangelist John Guest came to campus and boldly challenged protestors for their inability to morally reason, Keller was there.8 At the same time, he was disenchanted with “orthodox Christianity” which he believed supported things like segregation and apartheid.9 Fortunately, for Keller, the evangelical left offered a version of the faith which married the ethics of the New Left with the metaphysical foundation Christianity provided. He began to realize he could have both.

Keller wrote that things began to change for him after finding a “band of brothers” who grounded their concern for justice in the character of God.10 He became part of a “campus fellowship” sponsored by InterVarsity which reflected the counterculture mindset of Bucknell by keeping their ministry non-traditional, “spontaneous,” and anti-institutional. It was there Keller first truly “came to Christ.”11 He also learned to navigate the cultural battle between people against “commie pinkos” “rabble-rousing in the street” and the radicals who protested on those streets.

In 1970, Keller heard a message which revolutionized his approach to political issues. Some of his friends attended InterVarsity’s Missions Conference called “Urbana 70″ where the Harlem evangelist, Tom Skinner, spoke about a “revolutionary” Jesus who was incompatible with “Americanism.”12 Skinner taught that the evangelical church had upheld slavery in the nation’s political, economic, and religious systems. While greedy landlords paid off corrupt building inspectors, police forces maintained the “interests of white society,” and the top one percent controlled the entire economy, evangelicals were silent and even supported the “industrial complex.”13 The 20-year-old Keller already resonated with the New Left critique, but Skinner’s way of incorporating it into Christianity was new for him.

His friends gave him a tape recording of Skinner’s talk and Keller “could not listen to this sermon enough.”14 Skinner claimed that a “gospel” that did not “speak to the issue of enslavement,” “injustice,” or “inequality” was “not the gospel.” Instead, he fused the incomplete gospels of both “fundamentalists” and “liberals” into a salvation which delivered from both personal and systemic evil. Jesus had come “to change the system” and Christians were to preach “liberation to oppressed people.”15 The sermon astounded Keller. It was just the kind of reconciliation he was waiting for and it left him unable to “think about politics the same way again” after hearing it.16 Tom Skinner, however, was not the only voice which helped Keller cultivate New Left ideas in Christian soil.

After graduating from Bucknell, Keller worked for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship in Boston, Massachusetts, and attended Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary where he met fellow seminarian Elward Ellis. Ellis was a student leader for InterVarsity and had previously been a “key leader in recruiting black students to attend Urbana 70 through a film that he wrote and produced” entitled, “What Went Down at Urbana 67.”17 The film challenged the notion that missions was “Christian racism” and promoted the idea that those of non-European descent could “preach the gospel the way it should be,” instead of the “honkified way of preaching the gospel.”18 Carl Ellis, an InterVarsity leader who had “enlisted Tom Skinner as a speaker” for the event, narrated the video.19 Like Skinner, Elward Ellis also imported New Left thinking into Christianity.

Ellis introduced Keller to concepts now referred to as “systemic racism” and “white privilege” by showing him that “white folks did not have to be personally bigoted … in order to support social, educational, judicial, and economic systems and customs that automatically privileged whites over others.”20 On one occasion Ellis called Keller a “racist” even though he admitted that Keller didn’t “mean to be” or “want to be.” Ellis told Keller that he simply could not “really help it” since Keller was blind to his own “cultural biases” which he used to judge “people of other races.”21 White Christians, Ellis maintained, practiced discrimination by making their “cultural preferences,” such as singing and preaching styles, “normative for everyone.” White people, in general, were also ignorant of the hardships racial minorities underwent in navigating “Euro-white culture.”22 Keller gladly accepted Ellis’s “bare-knuckled mentoring about the realities of injustice in American culture.”23 He now understood, in greater detail, certain aspects of the New Left critique, but still needed to further develop a Christian response to the unjust status quo. But first, he needed a job.

In 1975, Tim Keller married his wife Kathy at the beginning of his final semester at Gordon-Conwell. After graduation, he was ordained in the Presbyterian Church of America (PCA) and moved to Virginia where he pastored a church in a “blue-collar, Southern town.” He also served as a regional director of church planting for the PCA. Somehow, in the midst of his busy schedule, Keller also managed to take courses from Westminster Theological Seminary where he earned a Doctor of Ministry degree in 1981. Three years later, he moved to Philadelphia to take a job teaching at Westminster.24 It was there he met Harvie Conn, a professor of missions who helped Keller take the next step in marrying his social justice concerns with his Christian faith.

Some considered Conn a “bit of a radical” for challenging the interpretations of “white Presbyterian males” based on their allegedly biased cultural presuppositions.25 Instead, he believed in a “contextual approach” he referred to as a “hermeneutical spiral” for interpreting the Bible. This approach combined interpretation and application by emphasizing “the cultural contexts of the biblical text and the contemporary readers” which called for a “dialogue between the two” in a “dynamic interplay between text and interpreters.”26 Of course, this method of interpretation denied “objectivism” and the “classic pattern of historic-grammatical exegesis.” Because “sociological and economic preconceptions” influenced ones interpretation of the Bible and the world, Conn affirmed, along with “liberation theologians,” a “need for new input from sociology, economics, and politics in the doing of theology and missions.”27 In short, Conn believed that the experience of social groups helped determine the meaning and application of a text. Not surprisingly, this approach opened the door for new ways of understanding the Bible.

Liberation theology, which used Marxism as an “instrument of social analysis,” awakened Conn’s own conscience to the realities of oppression. He believed that “a bias toward the poor, the doing of justice, [and] the battle against racism,” were necessary starting points for properly interpreting Scripture.28 After all, Jesus, who Conn described as a “refugee” and “immigrant,” “identified with the poor.” Therefore, members of His kingdom must also show “solidarity with the poor” in their personal life and social perspective.29 Instead, White American evangelicals identified with “saints” and required the “world” to come on the church’s terms. Not surprisingly, Conn thought “the church must recapture its identity as the only organization in the world that exists for the sake of its nonmembers” and “repent” for things like neglect of the “urban poor,” “dull, repetitious, [and] unexciting” services, and hypocrisy.30

In order to follow Conn’s advice, churches needed to engage in “holistic evangelism,” which included working to eliminate “war and poverty and injustice” with a “full gospel” which addressed social questions.31 Charity alone was not enough.32 In fact, the gospel possessed its own “political program based on its own analysis of the global reality of man.” Conn even believed that “certain socioeconomic commitments [came] closer to certain features of the gospel than others.”33 This broadening of the gospel message and evangelistic task included a fusion of liberation theology, and perhaps Kuyperian thinking, with evangelicalism.34

Conn, who disparaged “wealth and whiteness” and compared Wall Street workers with prostitutes, certainly had little affinity for “capitalism,” which he believed provided “myths” for understanding “social needs.” At the same time, the “Marxist tool” was only useful insofar as it remained subservient to the “Lordship of Christ.”35 Liberation theologians “distorted” the role of the church by “making it into revolution.” But, they also challenged the “hidden ideologies” of “conservative evangelicals,” such as pietism and privatization, and could help “refine [their] commitment to the gospel.” Conn believed the problem with most evangelicals was they gave “the salvation of souls top priority and the concern for social justice only secondary and derived importance.”36 Instead, he pointed to members of the evangelical left such as Orlando Costas, Jim Wallis, John Perkins, Richard Mouw, and Ron Sider as positive examples of evangelicals who understood what the title of his 1982 book, Evangelism: Doing Justice and Preaching Grace, promoted.37

Tim Keller personally admired Harvie Conn and found his writings to be both “mind-blowing” and deeply impacting.38 Conn’s most famous contributions to missions were his writings on urban ministry. By using insights from “urban sociology, urban anthropology, and biblical theology,” Conn showed that cities were not the impersonal secular places evangelicals thought them to be.39 Actually, “the city” carried with it a special eschatological significance. Since the final chapter in human history culminated with the New Jerusalem, it represented a return to Eden. Temporal cities reflected aspects of both Eden and the restoration of Christ as places to “cultivate the earth,” “live in safety and security,” and “meet God.”40 Scripture taught that Jesus came to “redeem the city,” and it was the church’s job to join this special “kingdom story.”41 Conn’s strategy for evangelizing urban centers involved focusing on social groups, as opposed to individuals, and promoting cross-cultural interactions which served to help eliminate “racism, injustice, and discrimination.”42 Keller resonated with Conn’s ideas.

While teaching at Westminster, Keller developed his distinctively Dutch Reformed approach to missions and apologetics under the influence of Conn.43 The “life-changing impact” Conn had on him manifested itself in 1989 when Keller moved from Philadelphia with his wife and three sons to start Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. Keller wrote he would “never, ever, have been open to the idea of church planting in New York City if it were not for the books and example of Harvie Conn.”44 In facing the challenges of urban ministry, Keller appealed to many of Conn’s teachings including the priority of cultural contextualization, the hermeneutical spiral, and the eschatological significance of “the city.”45 Like Conn, Keller viewed influencing the city as a way of influencing the broader culture. He accepted Conn’s reconfiguration of the “cultural mandate” to fill, subdue, and rule the earth, as an “urban mandate.”46 Perhaps, most important for political purposes, Keller also deeply imbibed Conn’s awareness of “systemic injustice” and the themes surrounding his proposed Christian solution.47

Like most leaders of the early evangelical left, Keller’s main critique of Marxism was its materialism, not its moral claims. Karl Marx’s solutions were incorrect because he grounded them in atheism and ignored the reality of human sin.48 However, despite these major flaws, Keller believed Marxist hearts were in the right place. He stated in a sermon at Redeemer:

The people I read who were the disciples of Marx were not villains. They were not fools. They cared about people… there are vast populations, millions of people, who have been in absolute serfdom and peasantry and poverty for years and years, and there’s no way they’re going to get out. There’s no upward mobility. See, the people who read Marx said, ‘We have to do something about this.’ They weren’t fools.49

Keller also singled Karl Marx out as the only “major thinker,” other than God himself, who “held up the common worker” with a high view of labor.50 Unfortunately, for Marx and New Left thinkers downstream, like Ronald Dworkin, R. D. Laing, and Jean-Paul Sartre, their moral claims could not be justified apart from the moral foundation Christianity provided which had a “basis” for racial, social, and international justice.51 Like progressive evangelicals before him, Keller addressed this problem by combining aspects of New Left thinking with Christianity.

From Keller’s perspective, economics was a zero-sum game. Impoverished children suffered because of an “inequitable distribution” of “goods and opportunities,” not just a lack of them. Therefore, Christians who failed to share with the needy, were not only displaying “stinginess,” but “injustice” itself. For believers, this kind of work, unlike “charity,” was not optional. In fact, failing to share with the poor was tantamount to robbery because justice involved giving people their “rights” which included things like “access to opportunities,” “financial resources,” “access to education, legal assistance, [and] investment in job opportunities.” The principle of “private property,” however, was not an “absolute” right.52

In 2010, Keller told Christianity Today, “It’s biblical that we owe the poor as much of our money as we can possibly give away.” Using the language of moral obligation, he implied that the “have-nots,” on the basis of their need, possessed a legitimate claim to resources not distributed to them which belonged to the “haves.” The church’s job was to address these inequities by not only meeting needs, but also addressing “the conditions and social structures” that led to such needs in the first place. Keller pointed to liberation theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez’s teaching on God’s preference for the poor, and progressive evangelical John Perkin’s teaching on “redistribution” as positive examples. He encouraged churches to get involved in “direct relief, individual development, community development, racial reconciliation, and social reform” which challenged and changed “social systems.”53

In Keller’s model, the gospel itself became the basis for Christians to do this “restorative and redistributive justice.”54 It was both a response to the gospel, and a means by which believers attracted unbelievers to Christianity. According to Keller, this was not a new development either. He translated some Old Testament passages using the term “social justice” in the place of words that, in other translations, simply conveyed “righteousness” or “justice.” God, in Keller’s mind, charged Old Testament Israel to “create a culture of social justice.” The application of this command, in the Mosaic law, was designed to reduce “unjust” economic disparities between social groups. According to “the prophets,” “great disparities” resulted, at least in part, from a “selfish individualism” overcoming “concern for the common good.”55

In contrast, Jesus almost sounded like a “social justice radical activist” when he instructed selling possessions and giving to the poor in the Sermon on the Mount.56 Christians who understood God’s grace the best, were the “most sensitive to the social inequities,” and churches who were true to the gospel were “just as involved in social justice issues as in bringing people to radical conversion.” 57

Keller’s analysis for helping Christians battle disparities went deeper than just economic factors. Power relationships were also unequal. In his suffering, Jesus identified not only with the “poor,” but also the “marginalized” and “oppressed.”58 The “substitutionary atonement” involved Jesus losing His “power” which, in turn, inspired Christians to be “radical agent[s] for social change” by giving up theirs.59 The people of God were commanded to “administer true justice” to “groups [which] had no social power,” which in modern times Keller expanded to include refugees, migrant workers, homeless, many single parents, and the elderly.60 Much of his sermons on power relationships incorporated the teachings of Michel Foucault, who, according to Keller, was a “postmodern theorist,” “socialist,” and “French deconstructionist.”61

Keller stated that “the problem with the world” was “the way we use the truth” for the purpose of getting “power over other people.” He thought Foucault was not only “right,” but put it better than anyone else when he said, “Truth is a thing of this world: it is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint. And it induces regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts … the means by which each is sanctioned … the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true.” Keller summarized Foucault’s theory by stating, “truth is a thing of this world, and every person who claims to have the truth is really basically doing a power play.”62 He even quoted Jesus as stating, “Truth claims, in general, … are power plays”63 in reaction to the Pharisees who were guilty of using “the Bible to get the right places in society, the high status, and to keep people down.”64 Keller, along with “postmodern thinkers,” saw the “connection between truth and power” everywhere from discriminatory hiring practices to media narratives.65

In fact, from the Beatitudes, Keller believed Jesus taught that the quest for “power, success, comfort, and recognition” dominated the “kingdom of this world.”66 It even inescapably defined individuals themselves. New Left thinkers, like Foucault, saw in Hegel’s concept of the “Other,” a substitute for the alienation which took place at the Fall. Identity was not organically inherited or part of the fabric of duty and design, but rather, created through struggle against the “Other,” which represented a negative, usually social standard. 67 Keller stated, in reliance on Foucault, that when “we form an identity … we get a sense of self-worth by despising the people who don’t have it” which is the same as bolstering “a self through exclusion of the ‘Other.’” Simply put, people use their chosen identities, based on things like their work, religion, and political affiliation, to exert power by vilifying others who are “not like them.” Only in Christianity did Keller see “a basis” for “accepting” different people.

No revolution could escape the reality of power except “the Kingdom of God,” ruled by a “king without a quarter,” “power,” or “recognition,” and requiring his followers to give up their power as well.68 Keller saw Christianity as “a kind of truth” which empowered and liberated its believers to “serve and love others, not control them.”69 He agreed with liberation theologian James Cone that slaves, because of their “experience of oppression,” were able “to see things in the Bible” like a “God who comes down from heaven and becomes a poor human being,” which “many of their masters were blind to.” This difference in experience was so great it nurtured a “real Christianity” as opposed to the oppressive “Master’s religion.”70 Real Christianity was the escape hatch from the view that truth “inevitably leads to power,” as it not only addressed economic disparities, but also unequal power relationships.71 Therefore, the “church” could not ally or align itself with the “secular left or right” for the sake of “political power,” without giving up its “spiritual power and credibility with nonbelievers.”72 Christians needed a different political approach.

Because Christianity, in Keller’s view, grounded both personal ethics and social justice in a transcendent standard, it represented an unconventional political perspective outside of earthly political parties. Keller conceived of “liberal politics” as a philosophy dedicated to doing “whatever you want with your body but not whatever you want with your money.” Their concern was “economic justice” in “taking care of the poor.”73 Throughout his ministry Keller identified “social justice” concern with more politically progressive groups.74 On the other hand, “conservatives,” he told his congregation, wanted “legislation that supports the family” and “traditional values, but when it comes to giving money to the poor, that should be voluntary.” Liberals wanted to legislate “social morality” but not “personal morality” and conservatives wanted to legislate “personal morality” but not “social morality.”75 Neither represented an acceptable Christian position.

The problem with closely aligning with either political philosophy, according to Keller, was that they could easily culturally “colonize” Christians into versions of “extreme individualism.” The sexual rights of “blue state” individualism and the property rights of “red state” individualism were comparable to false religions coopting Christians into their mold.76 Blue evangelicals were “quiet about the biblical teaching” on “abortion, sexuality, and gender.” Red evangelicals were “silent” when “political allies fan[ned] the flames of racial resentment toward immigrants.” Keller wrote that “ Theologically, both political pols are suspect, because one makes an idol out of individual freedom, and the other makes an idol out of race and nation, blood and soil. In both something created and earthly is deified.”77Alternatively, Keller proposed a third option in the “biblical worldview.”78

While Christians could “vote across a spectrum” for practical reasons, they should also “feel somewhat uncomfortable in either political party.”79 The Bible deconstructed “all secular understandings of economics” including “capitalism [which] uses the engine of individuals envying individuals, and communism or socialism [which] just uses the engine of classes envying classes.”80 In order to be biblical, Keller thought consistent Christians would, in applying an understanding of justice and equality, “sometimes … side with one school of thought, [and] other times they will side with another” because secular theories of justice addressed certain “facets of biblical justice” without addressing them all.81 This of course meant Christians could “care for the poor” through “high taxes and government services” or “low taxes and private charity.”82 The biblical idea, that “the community has some claim on” private “profits and assets,” but that those items should not be “confiscated,” did “not fit well with either a capitalist or a socialist economy.”83 Instead, Christians needed to, on some level, politically operate outside the available political parties. This, of course, meant spending more effort distancing themselves from Republicans, whom evangelicals had traditionally supported, than it did Democrats, the party Keller himself was a member of.84

In 2017, Keller signed a statement, along with other more progressive-leaning evangelicals like Richard Mouw and Ed Stetzer, urging “President Trump to Reconsider Reduction in Refugee Resettlement.”85 The next year Keller, along with “50 evangelical Christian leaders,” including Jim Wallis, gathered at Wheaton College to discuss their concern that evangelicalism had “become too closely associated with President Trump’s polarizing politics.”86 In 2020, Keller briefly joined the elder board of the AND Campaign, led by “Michael Wear, one of President Obama’s former faith advisors, and Justin Giboney, a Democrat political strategist. The campaign produced a “2020 Presidential Election Statement” to “promote social justice and moral order” which included concern for “racial disparities,” support for the “Fairness for All Act,” “comprehensive immigration reform,” and “affordable health care,” while discouraging abortion.87

Keller’s political vision was perhaps most clearly articulated in his 2008 book, Reason for God, in which he signaled his hope that “younger Christians … could make the older form of culture wars obsolete” through their version of Christianity which is “much more concerned about the poor and social justice than Republicans have been, and at the same time much more concerned about upholding classic Christian moral and sexual ethics than Democrats have been.”88 Christianity offered an “identity” which prioritized service “instead of power.”89 A “new human society, a new human order, [and] a new set of social arrangements not based on power and pride” was on the horizon in what the Bible called “the lofty city.”90 The vision of Redeemer Presbyterian was “to help build a great city for all people through a movement of the gospel that brings personal conversion, community formation, social justice, and cultural renewal to New York City and, through it, the world.”91 From Keller’s perspective, the church occupied the same role that “voluntary associations” did in Saul Alinsky’s vision of “broad based community organizing.”92 He stated, “The whole purpose of salvation is to cleanse and purify this material world.”93

Some have tried to analyze Tim Keller’s social justice position as a subset of concerns stemming from his crafting “new lines of thought” for communicating with “postmoderns.”94 Michael Foucault was not the only postmodern New Left thinker Keller gleaned from in his ministry. For example, in crafting his New City Catechism, created to meet the challenges of a postmodern world, Keller partially relied on understandings gleaned from Charles Taylor’s “buffered self-narrative.”95 Keller also taught his congregation that Martin Heidegger’s theory of “alienation” paralleled Jesus’ teaching in the story of the Prodigal Son.96 In 2018, he helped launch the “Living Out Church Audit,” designed to help churches be inclusive toward “LGBTQ+/ same-sex attracted” individuals.97 Because of Keller’s non-traditional conceptions of sin, hell, the Trinity, the church’s mission, biblical interpretation, creation, and ecclesiology, a group of traditional Presbyterians wrote Engaging Keller, in 2013. However, there is another way to understand Keller’s left-leaning tendency.

From his earliest and most formative years as a Christian and theologian, Keller, who already stood politically with progressives, was influenced by the evangelical left. Tom Skinner, Elward Ellis, Harvie Conn, Richard Mouw, and John Perkins all contributed to helping Keller integrate his faith with his politics. Keller often interpreted scriptures concerning politics and economics in ways consistent with neo-Kuyperian and liberation theologies. Keller then successfully marketed his ideas to the evangelical world. Despite passing away in early 2024, the impact of Keller’s teachings have not diminished. The systems he established continue his work, and the impact of his teachings will be felt for years to come.

1 Tim Keller, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism, (New York: Dutton, 2008), xi.

2 Tim Keller, February 14, 1993, “Let Your Yes Be Yes,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive (New York City: Redeemer Presbyterian Church, 2013); Keller, May 2, 1993, “House of God—Part 3,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, The Reason for God, xi.

3 Keller, August, 26, 1990, “The Secret Siege of Nineveh,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, March 15, 1992, “Missions,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, May 1, 1994, “Who is This Jesus?,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

4 Tim Keller, Generous Justice How God’s Grace Makes Us Just, (East Rutherford: Penguin Publishing Group, 2010), loc 151–160, Kindle.

5 Keller, May 27, 1990, “Christian Experience & Counterfeit,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, February 5, 1995, “Loving and Growing—Part 2,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive. Keller, September 3, 1989, “Politics of the King,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

6 Keller, October 7, 1990, “Spiritual Gifts—Part3,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

7 Tim Keller, Encounters with Jesus Unexpected Answers to Life’s Biggest Questions (East Rutherford: Penguin Publishing Group, 2013), xv; Keller, Generous Justice, loc 160–167.

8 Keller, March 25, 1990, “Goodness and Faithfulness,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

9 Keller, The Reason for God, xii.

10 Ibid., xii.

11 Keller, August 5, 1990, “Blueprint for Revival: Introduction—Part 2,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

12 Keller, February 23, 1997, “With a Politician,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

13 Tom Skinner, “The U.S. Racial Crisis and World Evangelism,” (Speech delivered at Urbana Student Missions Conference, Urbana, Illinois, 1970). https://urbana.org/message/us-racial-crisis-and-world-evangelism.

14 Keller, “With a Politician.”

15 Skinner,“The U.S. Racial Crisis and World Evangelism.”

16 Keller, March 11, 2007, “Jesus and Politics,” The Timothy Keller Sermon Archive.

17 Gordon Govier, “In Remembrance – Elward Ellis,” InterVarsity, May 14, 2012, https://intervarsity.org/news/remembrance-%E2%80%93-elward-ellis.

18 “What Went Down at Urbana 67 — Urbana 70 Black Student Promotional,” (Ken Anderson Films), accessed August 15, 2020, 2:30, 13:05, https://vimeo.com/42230364.

19 David Swartz, Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), loc 573–581, Kindle.

20 Irwyn Ince Jr, The Beautiful Community: Unity, Diversity, and the Church at Its Best (InterVarsity Press, 2020), 2.

21 Keller, Generous Justice, loc 168–180.

22 Tim Keller, forward to The Beautiful Community: Unity, Diversity, and the Church at Its Best, 3.

23 Keller, Generous Justice, loc 168–180.

24 Keller, October 31, 1993, “The Battle for the Heart,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; “Tim Keller,” Cruciformity Shaped By The Cross: Christian Life Conference 2007, February 18, 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20070218113355/http://clc.2pc.org/index.php/tim-keller/.

25 Peter Enns, “The (Or at Least ‘A’) Problem with Evangelical White Churches,” Patheos (blog), July 2, 2015, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/peterenns/2015/07/the-or-at-least-a-problem-with-evangelical-white-churches/; Mark Gornik, “The Legacy of Harvie M. Conn,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 35, no. 4 (October 2011), 214.

26 Harvie Conn, “Theologies of Liberation: Toward a Common View,” Tensions in Contemporary Theology, Third (Moody Press, 1979), 420, 428.

27 Ibid., 413, 421–422.

28 Ibid., 334, 404–405.

29 Ibid., 419–420, 423.

30 Harvie Conn, Evangelism: Doing Justice and Preaching Grace (Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan Pub. House, 1982), 23–24.

31 Ibid., 56, 73–74.

32 Harvie Conn, A Clarified Vision for Urban Mission: Dispelling the Urban Stereotypes (Ministry Resources Library, 1987), 147.

33 Conn, “Theologies of Liberation,” 416.

34 Conn, A Clarified Vision for Urban Mission, 142, 147.

35 Conn, “Theologies of Liberation,” 413–414, 425.

36 Ibid., 413, 409–410, 418

37 Ibid., 34, 50, 52, 73, 79.

38 Tim Keller, “Westminster — In Memory of Dr. Harvie Conn,” Westminster Faculty, August 15, 2000, https://web.archive.org/web/20000815221157/http://www.wts.edu/news/conn.html.

39 Conn, A Clarified Vision for Urban Mission, 9–10.

40 Tim Keller, Loving the City: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City (Zondervan, 2016), 310.

41 Gornik, “The Legacy of Harvie M. Conn,” 214.

42 Conn, A Clarified Vision for Urban Mission, 217–218.

43 Keller, Loving the City, 104–105.

44 Keller, “Westminster — In Memory of Dr. Harvie Conn.”

45 Keller, Loving the City, 106, 46; Tim Keller, Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City (Zondervan, 2012), 10; Tim Keller, Gospel in Life Study Guide: Grace Changes Everything (Zondervan, 2013), 127; Tim Keller, Jan 7, 2001, “Lord of the City,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

46 Keller, Loving the City, 148, 134.

47 Keller, Generous Justice, 189.

48 Keller, February 16, 1997, “With a Religious Crowd,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, October 22, 2000, “Made For Stewardship,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, July, 15, 2001, “Arguing About Politics,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

49 Keller, “With a Religious Crowd.”

50 Keller, “Made for Stewardship.”

51 Keller, The Reason for God, 151–152; Keller, May 31, 1992, “Problem of Meaning; Is There Any Reason for Existence?,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, “Center Church,” 129; Keller, December 10, 2000, “Genesis—The Gospel According to God,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

52 Tim Keller [@timkellernyc], 2018, “The Bible’s vision for interdependent community, in which private property is important but not an absolute, does not give a full support to any conventional political-economic agenda. It sits in critical judgment on them all.,” Twitter, November 8, 2018, 11:26 a.m.

53 Keller, Generous Justice, 15, 92, 3, 115, 16–17, 125–126, 7, 117, 130–133; Tim Keller, “Tim Keller’s Generous Justice,” interview by Kristen Scharold, December 6, 2010, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2010/december/10.69.html.

54 Keller, The Reason for God, 225.

55 Keller, Generous Justice, 356–366, 139, 9, 33–34.

56 Keller, May 9, 1999, “The Mount, Life in the Kingdom,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

57 Keller, Generous Justice, xxiv; Keller, November 9, 2003, “A Woman, A Slave, and a Gentile,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

58 Keller, Reason for God, 195–196.

59 Keller, March 11 2007, “Jesus and Politics,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

60 Keller, Generous Justice, 4.

61 Keller, October 5, 2003, “The Meaning of the City,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, “Arguing About Politics;” October 10, 1993, “The Search for Identity,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

62 Keller, “The Meaning of the City.”

63 Keller, October 8, 2006; “Absolutism: Don’t We All Have to Find Truth for Ourselves?,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

64 Keller, May 16, 2010, “Integrity,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

65 Keller, March 3, 2002, “Passionate Grace,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

66 Keller, “Arguing About Politics.”

67 Roger Scruton, Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), 74–76.

68 Keller, “Arguing About Politics.”

69 Keller, “Passionate Grace.”

70 Keller, May 31, 2000, “What is Freedom” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, May, 3, 1998, “My God is a Rock; Listening to the African-American Spirituals,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

71 Keller, “Passionate Grace.”

72 Tim Keller, Forward to In Search of the Common Good: Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World (InterVarsity Press, 2019), 3.

73 Keller, March 25, 1990, “Goodness, Faithfulness,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

74 Keller, April 24, 2005, “The Community of Grace,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive; Keller, March 19, 2006, “The Openness of the Kingdom.” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

75 Keller, “Goodness, Faithfulness.”

76 “Tim Keller on Changing the Culture Without Being Colonized by It,” (The Gospel Coalition, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=4&v=eDqJkfhTuRY&feature=emb_title.

77 Tim Keller, Forward to In Search of the Common Good: Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World.

78 “Tim Keller on Changing the Culture Without Being Colonized by It.”

79 Keller, “Arguing About Politics;” “You Need to Hear Tim Keller’s Takedown of Radical Nationalism,” Relevant Magazine (blog), December 10, 2018, https://relevantmagazine.com/current/you-need-to-hear-tim-kellers-takedown-of-radical-nationalism/.

80 Keller, “Arguing About Politics;” Keller, September 27, 1998, “When All You’ve Ever Wanted Isn’t Enough,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

81 Keller, Generous Justice, 159; Tim Keller, “A Biblical Critique of Secular Justice and Critical Theory,” Life in the Gospel, July 31, 2020, https://quarterly.gospelinlife.com/a‑biblical-critique-of-secular-justice-and-critical-theory/.

82 Tim Keller [@timkellernyc], 2020, “Christians and the freedom of conscience in politics. The Bible binds my conscience to care for the poor, but it does not tell me the best practical way to do it. Any particular strategy (high taxes and government services vs low taxes and private charity) may be good and wise…,” Sept 16, 2020, 9:15 p.m., https://twitter.com/timkellernyc/status/1306401474222620672

83 Keller, A Biblical Critique of Secular Justice and Critical Theory.”

84 Michael Foust, “Tim Keller Explains Why He’s a Registered Democrat: It’s ‘Smart Voting’ and Strategic,” Christian Headlines, November 4, 2020, https://www.christianheadlines.com/contributors/michael-foust/tim-keller-explains-why-hes-a-registered-democrat-its-smart-voting-and-strategic.html.

85 “Evangelical Leaders from All 50 States Urge President Trump to Reconsider Reduction in Refugee Resettlement,” The Washington Post, February 3, 2017, sec. A18.

86 Emily McFarlan Miller, “Evangelical Leaders Gather at Wheaton to Discuss Future of the Movement in Trump Era,” Sojourners, April 17, 2018, https://sojo.net/articles/evangelical-leaders-gather-wheaton-discuss-future-movement-trump-era.

87 “AND Campaign,” AND Campaign, accessed May 1, 2020, https://andcampaign.org

88 Keller, Reason for God, xix-xx.

89 Keller, February 25, 2001, “Born into Community,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

90 Keller, May 1, 2005, “The City of God,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

91 Keller, September 18, 2005, “Christ, Our Life,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

92 Grace, Justice, & Mercy: An Evening with Bryan Stevenson & Rev. Tim Keller Q &A (Redeemer Presbyterian Church, 2016), 31:30.

93 Tim Keller, “Cultural Renewal: The Role of the Intrapreneur and the Entrepreneur” (Entrepreneurship Forum, Lamb’s Ballroom, Times Square, March 25, 2006), 4:30, 9. https://web.archive.org/web/20060622051746/http://www.faithandwork.org/uploads/photos/461–1%20Cultural%20Renewal_%20The%20Role%20of%20th.mp3.

94 Ian Campbell and William Schweitzer, Engaging with Keller: Thinking Through the Theology of an Influential Evangelical (EP Books, 2013), 9, 21.

95 Tim Keller, “Catechesis for a Secular Age,” interview by James K.A. Smith, September 1, 2017, https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/catechesis-for-a-secular-age/.

96 Keller, November 2, 2008, “We Had to Celebrate,” The Tim Keller Sermon Archive.

97 “The Living Out Church Audit,” Living Out, accessed August 21, 2020, https://www.livingout.org/resources/the-living-out-church-audit.